If you’re new to this Substack, one of the things I’m offering subscribers in 2023 is A Year with Jane. We’re reading through Austen’s six novels this year and Sense & Sensibility is our read for August and September.

This is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

And psst! During September you can become a paid subscriber for 20% off for the next 12 months!

Is personality type the key to understanding people?

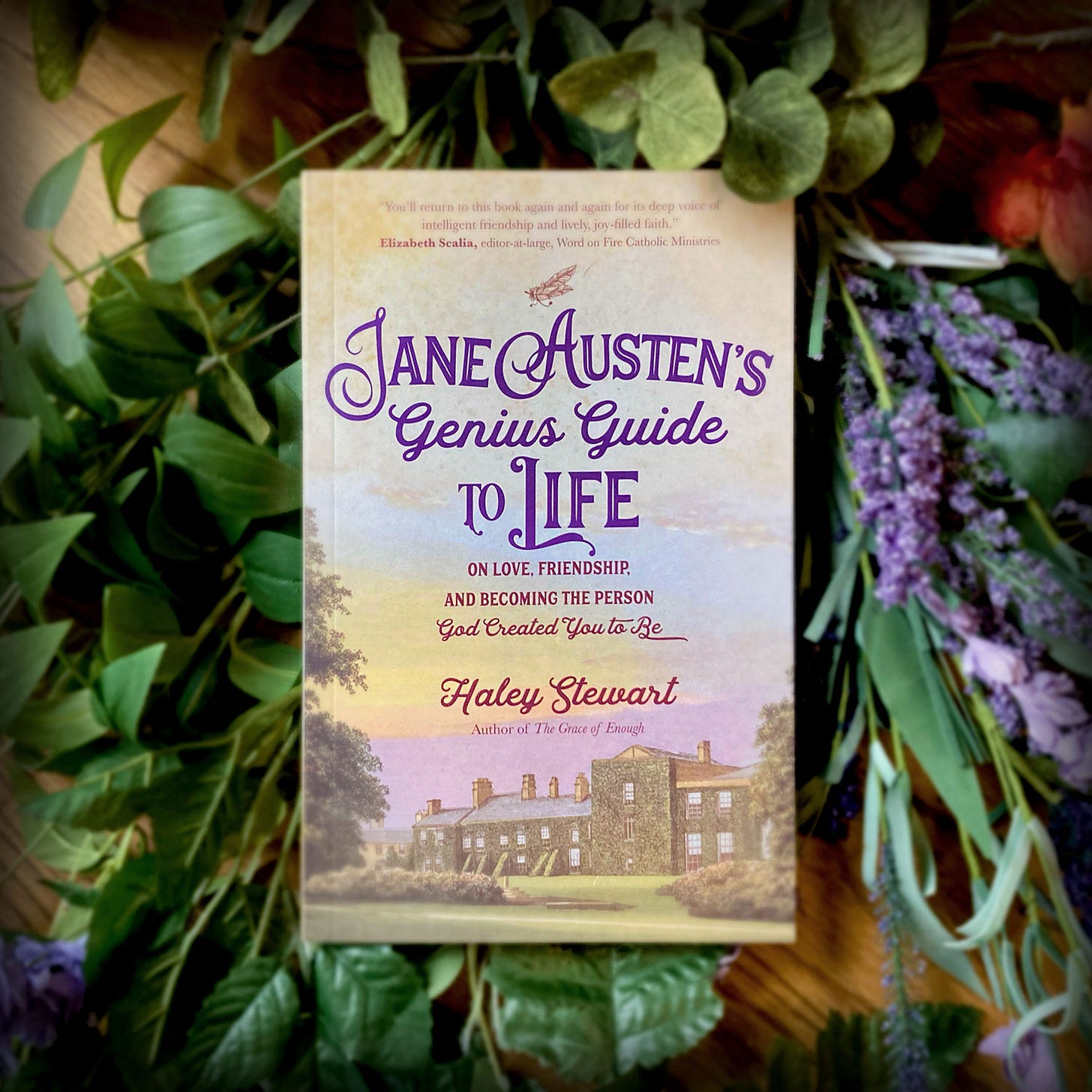

It’s our final reflection on Sense & Sensibility—a novel that, at its heart, is about two sisters. In my book, Jane Austen’s Genius Guide to Life, I discuss the virtue of temperance in the story and how to understand it in light of temperaments. Elinor and Marianne Dashwood’s temperaments couldn’t be more different. By temperaments, I mean their God-given personalities. I’ve always been fascinated by personality types as a way of learning to understand oneself and other people. It can be very helpful to understand things such as introversion versus extroversion: do you recharge by yourself or from interaction with others? If we know what helps us recharge, we can prioritize it for our own well-being. And if we know what helps others recharge, we can understand their behavior and avoid unnecessary conflict. An introvert needs their alone time, but an extrovert can fail to understand this need and interpret their desire for quiet recharging as anti-social. Marianne often misinterprets Elinor’s behavior and misjudges the depth of her emotions because she is more reserved than Marianne. She thinks Elinor is “cold-hearted” when, in fact, she is very emotionally invested—she simply does not outwardly reveal those feelings to every passerby. There is great value to understanding the temperament we are born with and how others are wired as well.

Using the Myers-Briggs personality types to consider the Dashwood sisters, I would guess that Marianne is an ENFP and that Elinor is an ISTJ—opposites! Marianne decisions are highly emotionally-driven, Elinor discerns with her head. Marianne is romantic, Elinor is highly practical. Regardless of the circumstances of their upbringing, this is just their natural bent. One is not right and the other wrong. And there is a limit to how these labels and categories can be helpful because they do not share the whole story with us. They cannot offer us the key to understanding our deepest selves because we are more than our temperaments.

Building a character

Our temperaments may be what we start out with, the ingredients we’re given, but we have to form them into a “character” that is strengthened or weakened over time through our moral education and habits. Character-building is what leads to becoming “our best selves,” to use a popular turn of phrase. Remember Henry and Mary Crawford from Mansfield Park? All the “ingredients” were in place, but they didn’t follow a good recipe of character building. Not only do they end up hurting others, we pity them for not becoming the people they could have been. What a waste!

We might feel the same way about Willoughby. Where did he go wrong? Was he given no guidance in building his self-control (temperance) to avoid becoming completely swept away by every whim of pleasure? We know he could have turned out better. He could have become someone worthy of Marianne.

We all need exemplars, or models of virtue, in order to order our temperaments and become people of good character. While Mrs. Dashwood is well-intentioned and affectionate (she’s certainly not a villain!), she does not offer Marianne clear guidance and example for reining in her emotions for her own good and the good of others. And Marianne dismisses Elinor’s example, misreading her temperance and prudence for lack of feeling.

For me, the most moving scene in the book is when Marianne, now recovered from her illness, tells her sister that she now sees the failings in her own behavior. Elinor asks, “Do you compare your behavior to his?” And Marianne replies, “No, I compare it to what it ought to have been; I compare it with yours.” Through suffering, Marianne has grown wise and this wisdom leads to a closer understanding between the sisters. Marianne sees that Elinor’s prudent behavior was not due to being unemotional. It required hard work, motivated by her love for others and respect for herself.

Are emotions bad?

Is a temperament given to strong feelings inferior to one trending more rational? Does Jane Austen think we should all be very buttoned-up and unemotional? No, indeed. We are meant to love Marianne for her sensitivity, as Colonel Brandon loves her for it. We are meant to imagine that her strong feelings can be ordered in a better way leading her to become a passionate (and compassionate) wife, mother, sister, daughter, and friend.

Philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre says in his masterpiece After Virtue: “Morality in Jane Austen is never the mere inhibition and regulation of the passions; although that is how it may appear to those such as Marianne Dashwood. . . Morality is rather meant to educate the passions.”

Each of us is unique and unrepeatable. We are wired the way we are to give glory to God and our temperaments are not bad or wrong. But they must be formed and ordered well. In the saints we see temperaments a bit like Marianne’s, the sensitive St. Therese of Lisieux, for example, leading to a passionate kind of holiness fueled with love for God. St. Therese didn’t get rid of her strong emotions. Instead, those tendencies were refined and offered as a special way of knowing and loving God and others. She just learned not to let herself be governed by her feelings.

In the same day, we wouldn’t want Marianne to be a different person—unemotional or reserved. We want her to be fully herself and that means the best version of herself: full of passion, moved by beauty, and deeply devoted to the people she loves.

Discussion Question: Marianne’s growth is obvious in the story, but does Elinor also change and grow?

(Chime in by replying to this post.)

Reading schedule:

August 5th:

Gather your books. There are many editions out there, so just grab what’s on your shelf or at the local library. And if you enjoy audiobooks, this is an excellent novel to enjoy with a great narrator. My favorite for this novel is Juliet Stevenson’s audiobook version. Grab Jane Austen’s Genius Guide to Life from Ave Maria Press (use STEWART20 for 20% off) or from Amazon.

If you didn’t start reading with us in January, you may want to catch up by reading the Introduction and Chapters 1-4 of Jane Austen’s Genius Guide to Life to set the stage.

Read by August 13th:

Chapters 1-11 of Sense & Sensibility

Read by August 20th:

Chapters 12-22 of Sense & Sensibility

Read by August 27th:

Chapters 23-29 of Sense & Sensibility

Read by September 3rd:

Chapters 30-36 of Sense & Sensibility

Read by September 10th:

Chapters 37-43 of Sense & Sensibility

Read by September 17th:

Chapters 44-50 of Sense & Sensibility

Read by September 24th:

Chapter 5 of Jane Austen’s Genius Guide to Life

NEXT UP: Northanger Abbey! We’ll read the whole novel in October, so grab a copy and start reading. Schedule and details coming soon.

All Jane Austen book club emails and 2023 emails will continue to be available with a free subscription. But this is a reader supported effort. Consider supporting this literary Substack by upgrading to a paid subscription.

And if you know someone who would love this virtual book club, please share with them:

Enjoy reading the next few chapters of Sense & Sensibility!

Haley

(Editor of Word on Fire Spark, Author, Former Podcaster)

Haley’s Children’s Mystery Series about Mouse Nuns

Haley’s Book on Jane Austen’s Novels

Haley’s Book about Radical Simplicity

Although it’s much more subtle than Marianne’s character growth, I think Elinor does change and grow by the end of the story. She’s so practical and steady and self-aware throughout the novel that I had to stop and contemplate her character for a while before answering (which is probably the intent of the question - ha!). Through her experience of watching her sister’s struggles while silently enduring her own, and then having the climactic confrontation with Willoughby while Marianne is in danger of dying, I think that Elinor is more prepared to share her wisdom and speak her mind than she is at the beginning of the novel, when she occasionally is hesitant about if and how to approach Marianne about her concerns. So while Elinor’s ups and downs aren’t as outwardly drastic as Marianne’s, I do think that she comes into her strengths as a character and grows in her confidence as a strong woman worthy of emulation.

This is just so good, Haley. You put it so well - that important distinction between understanding temperament and developing character. So many of us end up feeling trapped by our inherent temperaments instead of seeing them as unique opportunities to grow in particular virtues.

I also got a little teary thinking of that scene with Marianne and Elinor - gets me every time.