Chaos Is Dull: G.K. Chesterton and Detective Fiction (Part III)

Father Brown, Flawed Detectives, and Modern Enchantment

This series is drawn from a talk I gave at this year’s Chesterton Conference in Minneapolis. I’m hoping to share more pieces like this for my Substack subscribers in addition to This Week’s Miscellany and weekly Jane Austen reflections. If you’re not a subscriber, it’s a great time to subscribe.

Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

In Part One, I reflected on G.K. Chesterton’s claim in his strange detective story, The Man Who Was Thursday, that “chaos is dull.” Order is what makes poetry and art possible. In Part Two I considered the structure of detective fiction, what it has to do with fairy tales, and why we’re drawn to it. And now for Part Three!

Let’s turn to Chesterton’s most famous detective: Father Brown. Chesterton wrote Father Brown stories between 1910 and 1936. This nondescript detective isn’t tall. He’s a bit round and he’s not anyone you’d really notice. He doesn’t come across as particularly clever (until the end of each story when you see how he worked out the mystery). He seems unremarkable except that he’s an amateur detective who is also a Catholic priest. His ordinaryness is a gift to his investigation—he’s simply around and nobody seems to pay him much attention. But his priesthood is his biggest asset in solving crime because it has given him such insight into the human heart—and not only insight but compassion.

W.H. Auden has a wonderful essay about detective fiction called “The Guilty Vicarage” and he writes,

“Completely satisfactory detectives are extremely rare. Indeed, I only know of three: Sherlock Holmes(Conan Doyle), Inspector French (Freeman Wills Crofts), and Father Brown (Chesterton).”

And of Father Brown he says,

“His activities as a detective are an incidental part of his activities as a priest who cares for souls. His prime motive is compassion, of which the guilty are in greater need than the innocent, and he investigates murders, not for his own sake, nor even for the sake of the innocent, but for the sake of the murderer who can save his soul if he will confess and repent. He solves his cases, not by approaching them objectively like a scientist or a policeman, but by subjectively imagining himself to be the murderer, a process which is good not only for the murderer but for Father Brown himself because, as he says, “it gives a man his remorse beforehand.”

Father Brown’s simple humility, his acknowledgment that “there for the grace of God go I” is the key to solving mysteries that puzzle everyone else. And his compassion drives him. He is less interested in putting the criminal in jail as in leading him to contrition and saving his soul.

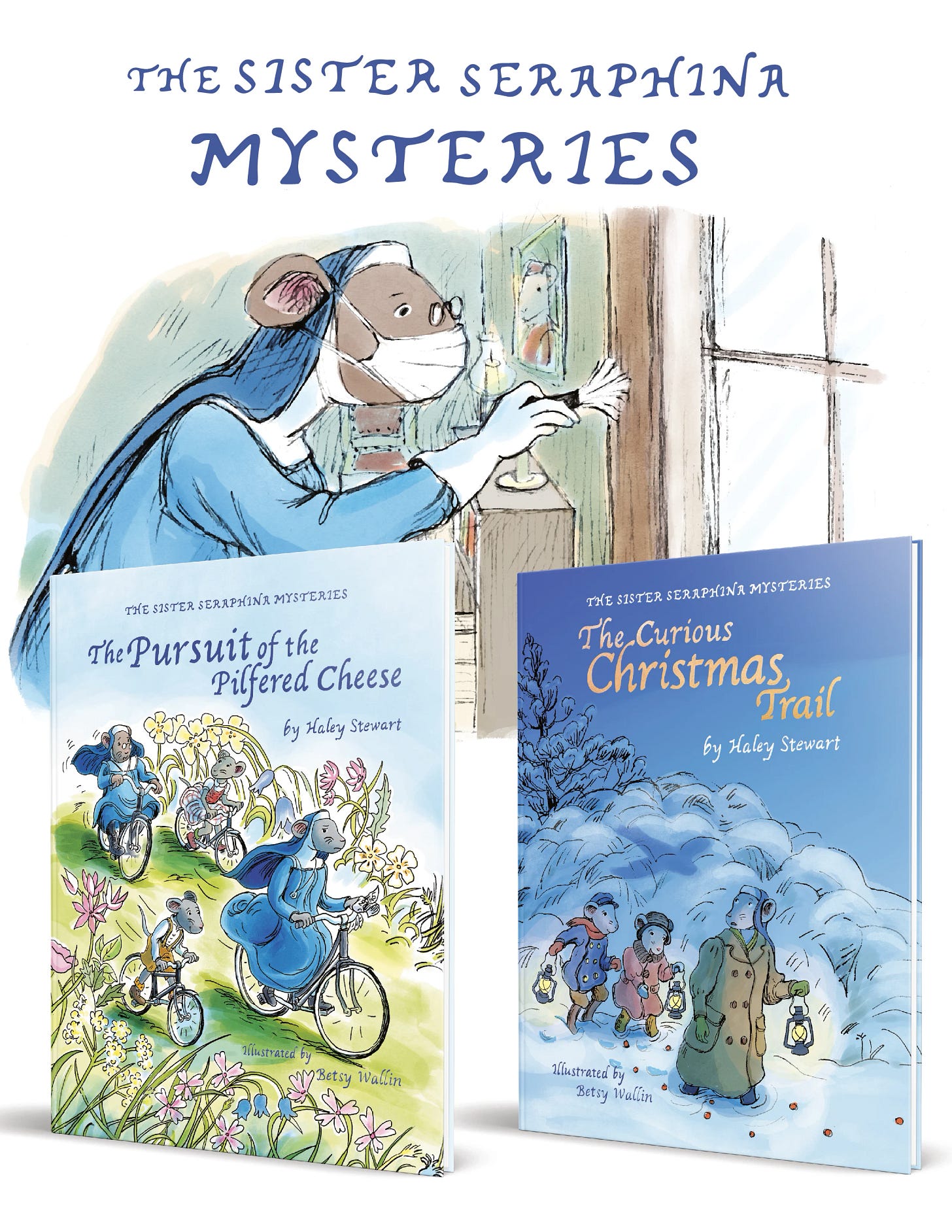

Chesterton’s Father Brown definitely influenced my own writing of detective fiction. The idea for my mystery series came to me in a dream. (I know this sounds like the kind of thing that writers make up, but it’s really true.) I dreamed about an order of mouse nuns who lived beneath G.K. Chesterton’s house. I often have vivid dreams, but they don’t usually turn into book ideas. But in this case, I dreamt of these little mouse nuns under Chesterton’s house and just couldn’t shake the idea. It started to grow and I thought that maybe their abbey of their order was underneath Chesterton’s floorboards and if that was the case, then surely they could hear him reading stories out loud. And perhaps they’d be particularly fond of Fr. Brown, because who wouldn’t be? And perhaps they would be inspired by an amateur detective like Fr. Brown who is also called to religious life and end up taking on some investigating themselves if a mystery were to emerge in the abbey—if they need to solve a local crime and the police inspector is out of town, for example.

So little by little the idea came together and then during Covid lockdown our little 1200 sq ft house with four children, a huge dog, and a grumpy cat seemed much smaller than usual. So I found myself hiding in our attic writing about mouse nuns as a bit of an escape from my darling and very loud children. And I just fell in love with Sister Seraphina, Sister Alberta, and Mother Alphonsa who run a school for village mice. And I wanted the sisters to be trustworthy, wise, and humble like Fr. Brown. And like Fr. Brown I wanted them to be compassionate when they encountered human weakness, but also courageous in protecting their students and restoring justice.

I started writing really not knowing where the story was going and who the villain was going to be and how the mystery would get resolved. But I just started following these little characters around and then a villain emerged that I think Chesterton would have appreciated. So I owe a debt to Chesterton and there’s a special place in my heart for Father Brown.

And I think there’s a little bit of Chesterton himself in Father Brown, because Father Brown seems to be in a constant state of wonder—something that shines out of Chesterton’s writings and one of the reasons we love to read him. By borrowing Chesterton’s vision we can experience wonder as well.

And it should be no surprise that Chesterton was drawn to detective stories. Because of their structure of order restored and sense of both the reality of sin and need for justice, detective mysteries in general are very Christian stories. Yann Martel, the author of Life of Pi, wrote some really compelling words about Agatha Christie, Chesterton’s fellow member of the Detection Club, but I think they could apply to the Father Brown stories as well.

Martel claims a close connection between both the morality of the Christian worldview and the structure of the narrative of detective fiction:

“The only modern genre that plays on the same high moral register as the Gospels is the lowly regarded murder mystery. If we set the murder mysteries of Agatha Christie atop the Gospels and shine a light through, we see correspondence and congruence, agreement and equivalence. We find matching patterns and narrative similarities. They are maps of the same city, parables of the same existence. They glow with the same moral transparency. And so the explanation for why Agatha Christie is the most popular author in the history of the world…she is a modern apostle…And this new apostle answers the same questions Jesus answered: What are we to do with death? Because murder mysteries are always resolved in the end, the mystery neatly dispelled. We must do the same with death in our lives: resolve it, give it meaning, put it in context, however hard that might be. And yet, Agatha Christie and the Gospels are different in a key way. We no longer live in an age of prophecy and miracle. We no longer have Jesus among us the way the people of the Gospels did. The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are narratives of presence. Agatha Christie’s are gospels of absence. They are modern gospels for a modern people, a people more suspicious, less willing to believe. And so Jesus is present only in fragments, in traces, cloaked and masked, obscured and hidden. But look–he’s right there in her last name. Mainly, though, he hovers, he whispers.”

In a great piece on Chesterton’s detective fiction, Lindsay Schlegel claims, “The mystery of creation and redemption, then, is exactly the sort of material that can be addressed in a detective story.” Chesterton himself calls the genre “the earliest and only form of popular literature in which is expressed some sense of the poetry of modern life.”

Chesterton speaks of detective fiction like a enchanting modern fairy tale:

“No one can have failed to notice that in these stories the hero or the investigator crosses London with something of the loneliness and liberty of a prince in a tale of elfland, that in the course of that incalculable journey the casual omnibus assumes the primal colours of a fairy ship. The lights of the city begin to glow like innumerable goblin eyes, since they are the guardians of some secret, however crude, which the writer knows and the reader does not. Every twist of the road is like a finger pointing to it; every fantastic skyline of chimney-pots seems wildly and derisively signalling the meaning of the mystery.

But have detective mysteries lost some of this enchantment? While detective stories remain very popular, I think there’s been a shift that says something about our narrative as a society in the 21st century. We’re still drawn to detective stories for the same reasons we always have been, the restoration of order is comforting in a world of chaos. We can’t help but navigate the world according to a moral code so we’re drawn to an environment in which morality is acknowledged. But there are some important shifts in the genre of detective fiction that are worth reflecting.

In many of the classic detective stories, the detective is almost godlike. He or she swoops in with sight that penetrates the problem at hand in a way that others cannot. The detectives mind is ordered in a special way. And they are remarkable because they bring order and justice with them wherever they go. Father Brown is always finding himself in strange circumstances, but wherever he treads justice is restored.

But modern mysteries can’t seem to abide a just and ordered detective. And I think it makes them less satisfying. Instead the drama revolves around the flaws of the detective himself. Instead of a sane figure coming to bring sanity to an environment of madness, it is a world of madness with a mad detective stumbling around in the dark.

And I don’t think that Chesterton would have liked this trend. In The Man Who Was Thursday he says, “For even the most dehumanised modern fantasies depend on some older and simpler figure; the adventures may be mad, but the adventurer must be sane. The dragon without St. George would not even be grotesque.” And in “The Dragon’s Grandmother” he writes, “In the fairy tales the cosmos goes mad; but the hero does not go mad. In the modern novels the hero is mad before the book begins, and suffers from the harsh steadiness and cruel sanity of the cosmos.”

There are many examples of this trend but the best might be a British series called Marcella. She’s an investigator going through a divorce and has fits of memory loss. She becomes unsure whether she herself is the murderer of her ex-husband’s girlfriend. Not only is she flawed or mad, but she may be the criminal. The lines are blurred. I find that interesting. There is no symbol of justice or order restored. It’s confusion and disorientation and chaos with no resolution.

I think another good example of this shift is in the character of Hercule Poirot in Agatha Christie’s novels versus Hercule Poirot in Kenneth Branagh’s films. In the films, Poirot has an extensive tragic backstory. His quirks are the result of trauma and Branagh seems to think it’s key for the audience to understand that. True Detective is another great (although highly disturbing) series in which the detectives are not sane men (they are not even just men) however they are able to participate in the restoration of justice despite being flawed. I find that more hopeful than Marcella. But I’m curious why we’ve shifted from a detective who is a reflection of the God who brings order from chaos to a detective who is as flawed as any other human and perhaps more than most. Do these kinds of stories ask if we, as flawed creatures, are capable of participating in restoring justice and order to a world of chaos? Would that be a hopeful question?

I’ve been reading a lot of author Katherine Paterson’s essays about writing for children lately and one thing she comes back to over and over again is the importance of hope in children’s books. She writes “Hope for us cannot simply be wishful thinking, nor can it be only the desire to grow up and take control of our own lives. Hope is a yearning rooted in reality that pulls us toward the radical biblical vision of the world remade.” What Paterson is calling for are stories that combat despair and cynicism. And this is not because the things that tempt us to despair aren’t real, but because they are real and we need a powerful source of hope to survive them. We need true stories.

Stories that end with a world set right help form our imagination to understand this deep truth that the universe is healed by love. This is not escapism, this is reality. Do we believe that ultimately there is hope or a final defeat? That we are not the result of mere chaos but created by a loving and just Father? That justice will reign over a broken world in the final chapter? Can detective fiction help us recognize these realities and remind us what kind of story we’re a part of? I think so—as long as it tells the truth.

“The word reveals the creator–and as our universe in its vastness, its orderliness, its exquisite detail, tells us something of the One who made it, so a work of fiction, for better or worse, will reveal the writer.” -Katherine Paterson

If you enjoyed this post, please share it. And if you find this Substack valuable, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

Very good insights. I’d like to recommend Emily Hanlon as an author with a wonderful modern spin on the God-like Catholic detective—not a priest but a quirky old church lady who always wears purple. The first book is called Who Am I to Judge?, and the series is the Martha and Marya Mysteries.

Haley,

As always, I so enjoy your thoughts in your newsletters. What a great “Part III” on Order and Chaos and the murder mystery! As I am currently reading the Cormoran Strike mysteries (by Robert Galbraith/J.K. Rowling), I have been wondering about the flawed detective who restores order in a chaotic world. Strike is definitely the “hero or the investigator [who] crosses London with something of the loneliness and liberty of a prince in a tale of elfland.” It would not surprise me to know Galbraith/Rowling knows these words by Chesterton.

Wondering if you have read The Cormoran Strike mysteries and if you think it a series that revolves around his flaws (at times, perhaps), or would you consider him a just and ordered detective? I am inclined to think the latter, especially as the series continues into its recently published 7th installment, however thought I would pose that question about a modern detective at the forefront of my reading.